Job creation during the 20th century

A long-term, global perspective is needed to understand fully the employment problem and the prospects for eliminating it. Over the past four decades, the world economy has generated more than one billion jobs, more than were created during the previous four centuries. If past trends continue, it will create another 1.3 billion jobs during the next 35 years. The current anxiety in the West is similar to that which the United States passed through in the 1890s when agricultural mechanization displaced 4.4 million farm workers, generating double digit unemployment and visions of a dismal future. Yet, over the last 100 years, employment in the United States grew by nearly 100 million jobs or 400 per cent. Between 1990 and 2005, it increased by another 23 million. Between 1990 and 2005, it increased by another 23 million. During the last 15 years, total employment in the EU-15 rose by 26.6 million or 19 percent. The same process of structural transition is repeating itself today and raising the same anxieties. Contrary to common belief, the US employment rate, the percentage of total population with jobs, has risen steadily throughout the century from 38 per cent to 46 per cent of the total population and reached 48 per cent in 2005.

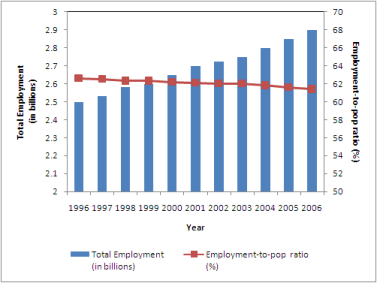

Global Population, Employment and Unemployment 1996-2006*

Source: ILO Global Employment Trends 2007(2006 are preliminary estimates)

OECD Countries

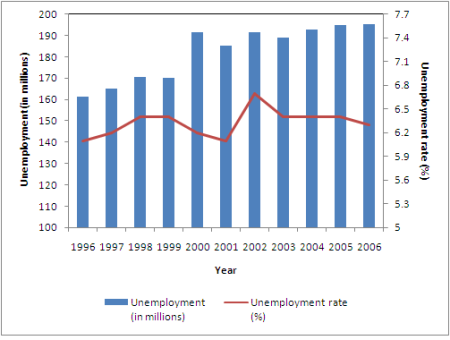

This trend is true for the industrial nations as a whole. Between 1960 and 2005, total employment in OECD countries rose by 452 million jobs (a 6.75 fold increase), which represents a 76 per cent increase in the proportion of the population employed, including a 45 per cent increase in the participation of women in the workforce.

During this same 45 year period, unemployment in OECD countries rose by only 33 million persons, equivalent to only 7 per cent of total job growth. More people are working than ever before. In absolute numbers, more people are unemployed, because the population is larger and a larger proportion of the population seek jobs.

These average figures disguise significant differences in performance of countries within the OECD. Since 1965, Japan's employment rate has risen dramatically from 46 per cent to 75 per cent of total population, while unemployment has risen from 1 per cent to around 3 percent. The overall proportion of the working age population employed in the European Union (EU15) has declined by 1.6 per cent since 1965 and is presently 65.4 per cent, whereas in other OECD regions it has risen significantly - to exceed 71 per cent in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Switzerland, Scandinavia, UK and USA. Europe's lower labour participation rate is attributable to a number of factors. A far higher percentage of the European workforce was engaged in agriculture 25 years ago and has since shifted to non-agricultural sectors, an adjustment that occurred in the United States during earlier decades. During the 1980s Europe chose a high-wage path to growth, passing on the benefits to the existing workforce but creating relatively few new jobs; whereas the United States, with a similar economic growth rate over the decade, showed lower income growth per worker, but a steadily rising employment rate. Europe is now confronted with the need for structural adjustment to compensate. Within the next decade, the aging of the population is expected to reduce job pressures and even lead to labour shortages in some European countries.

In the United States, the extent of the unemployment problem is partially disguised in the form of low-wage jobs, which distribute total income over a larger number of workers. Twenty per cent of all full-time US workers have incomes that fall below the official poverty line for a family of four, though only a quarter of these live in households whose total income is below the poverty line. Real wages in the United States have not risen significantly over the last 45 years due to the dramatic increase in the supply of labour as a result of 205 per cent increase in female participation since 1960 and the entrance of the baby-boom generation into the workforce. However, America's ‘family living standard' has still risen by 35 per cent in constant dollars since 1967.

Developing Countries

Job growth has been quite rapid in the developing countries over the last forty years, more than doubling total employment. The single most important factor behind rising numbers of unemployed persons and increasing absolute numbers of families below the poverty line in developing countries has been the 3.1 fold expansion of population in the Third World, and more than doubling of the economically active population since 1950, which have resulted in a 4 per cent decline in the overall employment rate. Population growth rates continue to fall steadily in most countries, with the exception of Africa, providing an opportunity for economic growth and job growth to catch up with the population explosion of recent decades.

Change in Quality of Employment

Along with rapid quantitative job growth, the global economy has achieved dramatic qualitative gains in the nature of employment. During recent decades, there has also been a marked movement away from subsistence level manual occupations, primarily in agriculture, to more skilled and remunerative forms of employment. Worldwide, the percentage of the work force engaged in agriculture has fallen by 34 per cent since 1950, from 67 to 44 per cent.

Economic Growth

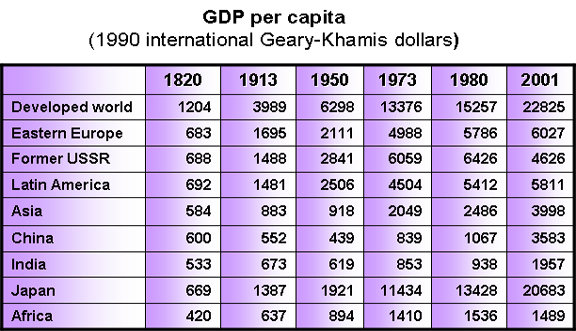

Over the past five decades, global GDP has multiplied seven-fold. In spite of unprecedented population growth, per capita income has more than tripled. Between 1950 and 2000, the world as a whole achieved unprecedented growth in real per capita income and consumption as reflected in the table below

Population & Employment

Unemployment is of growing concern today primarily because population has expanded in recent decades even faster than job creation and because a larger percentage of the population, principally women, seeks employment now than at any time in the past. The shortages of jobs and the resulting poverty represent the most pressing social problem in the world today. But when viewed in historical perspective, it is clear that substantial progress has been made during the post-war period, making humanity as a whole more prosperous than at any previous period in recorded history. Despite the paramount concern raised by the persistence of high rates of unemployment in recent years, available data do not confirm a long-term trend towards rising rates of global unemployment.

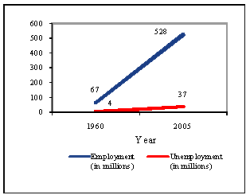

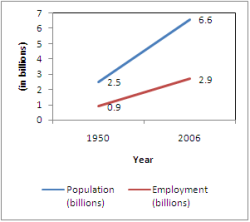

Between 1950 and 2006, global population increased from 2.5 billion to 6.6 billion, a growth of 164%. During the same period, total global employment rose from 900 million to 2.9 billion, a growth of 222%. More recently, between 1996 and 2006, global population increased by 766 million or 13 percent, while total global employment grew by 400 million or 16 percent.

These facts indicate the global job creation is taking place at record rates. In addition, this trend is taking place during a period in which the quality of work available has increased dramatically due to the replacement of manual work with mental work. To illustrate, during the past half century, the total percentage of humanity engaged in agriculture has declined from 35% to 38.7 percent in 2006.